At 8:04:00.0 Nevada time (15:04:00.0 GMT), on the 23rd of September 1992, the United States conducted its last nuclear test. The shot, codenamed Divider and conducted as part of Operation Julin, had a yield of 5 kt and was a Los Alamos National Laboratory device. Ten days prior, the US senate had passed 55-40, an amendment for a nine-month nuclear testing moratorium. On the 24th, one day after the test, this amendment passed congress 224-151. President Bush signed this moratorium into law on the 2nd of October 1992.[1]

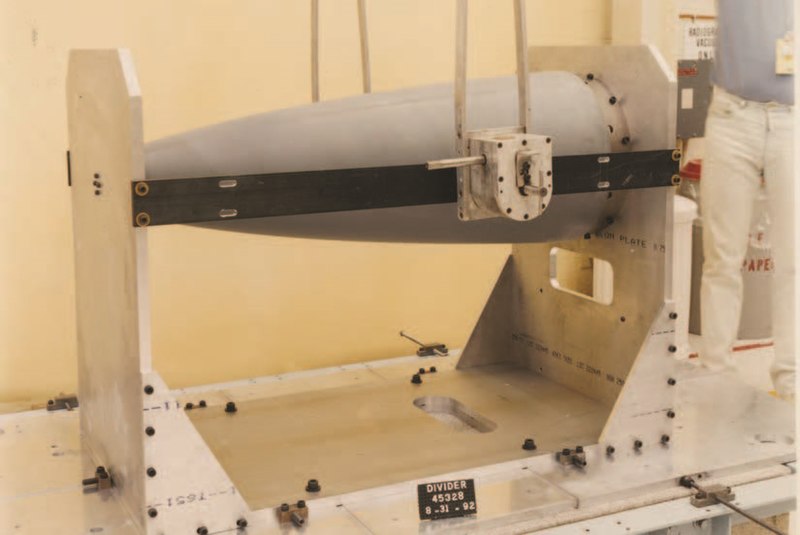

Figure 1 — Part of the Julin Divider diagnostic rack is assembled. Source.

The labs were apparently aware of a coming moratorium, and at the time were in the middle of a fifteen-shot series of “Hatfield compliant” nuclear tests designed to secure the nuclear arsenal for a long-term moratorium,[2] but it appears that they did not believe it would be so soon or that the nine-month moratorium would become an indefinite moratorium. At the very least, it appears that only the people near the top had any idea.[3]

Hatfield Compliance

It’s not clear to me the exact timeline of events, and I don’t really have much interest in the political minutiae of the matter to dive deeply into the topic. What is clear is that Republican senator Mark Hatfield was an advocate for the US nuclear testing moratorium. He led a bipartisan group of politicians in an unsuccessful attempt to create a moratorium in 1986 after the Soviet Union offered to suspend nuclear testing if the US also did so, and when Mikhail Gorbachev announced a Soviet unilateral moratorium on 5 October 1991, he began building political support for a US moratorium.[1] The Soviets had conducted their last nuclear tests — seven simultaneous tests — slightly less than a year previous, on 24 October 1990 at Novaya Zemlya.

It is unclear to me how Hatfield compliant testing came about. I suspect that he gained the support of several politicians on the condition that the Department of Energy be allowed to conduct a small number of tests before the moratorium. As the series was not completed, I presume he gained sufficient support elsewhere to enact a moratorium without these politicians’ support.

The Hatfield compliant test series was to consist of fifteen US tests and six British tests.[4] In a May 1993 letter to Hazel O’Leary, then Secretary of Energy, the directors of Los Alamos and Lawrence Livermore clearly expected nuclear testing to resume. This letter describes the Hatfield compliant test series as being fifteen tests, but only discusses options for six, seven and nine nuclear tests, consisting of one, six and two sub-options respectively.[4] I believe that this indicates that six tests had already been completed. If we look at the testing history, the US fired Julin Lubbock on 18 October 1991, and then did not fire another test until, Julin Junction, five months later on 26 March 1992, which began a string of six tests consisting of eight devices (Galena consisted of three devices). If Hatfield Complaint testing began between October and March, this would fit nine plus six.

What was actually tested and planned to be tested is not precisely clear. In the aforementioned letter to O’Leary, it is made clear that testing was to focus on four systems: the W76 and W88 warheads for Trident, the B61 bomb, and the W80 cruise missile warhead. This four-system concept was devised to provide safety backups for the four highest priority enduring stockpile systems. I presume this means the SLBM and ICBM warheads and not the four aforementioned systems, with the aforementioned being the backups.

However, it appears that the testing strategy was revaluated at the end of 1992 (i.e. after Divider). The labs “in principle” wished to create a backup using insensitive high explosive (IHE) and a fire-resistant pit (FRP) for the W76, but accepted that such a proposal would have a high level of technical risk given the limited number of tests allowed. The Department of Defense were apparently also strongly against a redesign of the W76.

Characteristically, most of the details are redacted from the letter. However, there are a surprisingly large number of details on planned W80 testing. The first was a plan for three safety development tests for the W80. The W80 has enhanced nuclear detonation safety (ENDS) and IHE, but lacked a FRP, they therefore proposed three W80 tests to develop a FRP for the weapon. It also notes that this weapon might be suitable for use in the Mark 5 reentry body (RB) used in the W88.

The second is a nine-test program for the W80 (presumably one of the two nine-test programs mentioned). The section is almost entirely redacted, other than one paragraph stating that “… implementation is the aim of this test program”. I presume that this is a test program to develop the W80 into a warhead more suitable for use in a reentry vehicle. This presumably includes the three tests to add a FRP and the remaining six tests would be to test warhead hardness to hostile weapon effects (ABM systems) and maybe to increase the yield (given its dual tactical/strategic role, the W80 might be a low-fission fraction design capable of being upgraded to a higher yield, but also dirtier weapon).

This appears to be supported by The US Nuclear Stockpile: Looking Ahead Drivers of, and Limits to, Change in a Test-Constrained Nuclear Stockpile (the infamous poorly redacted report I mentioned here), which states in regards to SLBM warheads over ICBM warheads “… the range of potential warhead replacement options is much broader”.[5, p. 23] It states that “either” (i.e. two) of the SLBM warhead protection program (SWPP) designs could also be used as backup for the ICBM role.[5, p. 24] The SWPP is specifically described as not being the W78, W80, W84 or B61-10.[5, p. 23] These SWPP warheads are probably the W89 and W91, but before the indefinite moratorium, it may have been planned for this upgraded W80 to be included.

Lawrence Livermore

The second to last nuclear test conducted by the United States, codenamed Hunters Trophy, was Lawrence Livermore’s last. It was a weapons effect test conducted in a tunnel, using an 850 ft (260 m) horizontal line-of-sight (HLOS) pipe.[3] At one end was the 4 kt device, and at the other was a number of items to be exposed to the radiation from a nuclear weapon. In between them was a vacuum to simulate outer space, and a number of FACs or fast-acting closures, designed to snap shut within milliseconds after the detonation and protect the items from the nuclear blast.

Figure 2 — The Hunters Trophy device is moved down N-tunnel to the emplacement site.[3]

A follow-up HLOS test, codenamed Mighty Uncle, was in the works and planned for 1993. The test was never conducted.[3]

Julin Divider

So, at the time of Divider, the labs were preparing for a moratorium and also looking at a W76 replacement, presumably using the same Mark 4 reentry body. Public details on the W76 are slim, but to the best of my knowledge, the W76/Mk4 and W68/Mk3 had the same length and base diameter (with the Mark 4 perhaps being slightly wider), and the Mark 3 was developed from the Halberd program. The Halberd RB was 46.64”(1185 mm) long and 13.4” (340 mm) wide at the base.[6, p. 10]

This is a very tight envelope to fit a warhead into and certainly too large for the W80 proposed for the Mark 5 RB. But it might have been large enough for Los Alamos’ W91 SRAM-T warhead.

Figure 3 — W89 SRAM-II warhead (top) and W91 SRAM-T warhead (bottom). Source.

I don’t have specific information on the W91’s dimensions, but the W89 which can be compared for scale was 40.8” (1036 mm) long and 13.3” (338 mm) in diameter.[7, p. 224] The W89 was 324 lb (147 kg) in weight, while the W91 was 312 lb (141.5 kg) in weight.[8, p. 13] I would estimate that once the rear hardware was redesigned for the role, another inch or two could have been shaved off.

So, what does this have to do with Divider? Well, to commemorate thirty years since the last US nuclear test, Los Alamos had a display on Divider. This display was not open to members of the public as it was located in a secure area, but it was unclassified.[9] So I sent an email to the Los Alamos library, asking if they could provide copies of the posters displayed, and they sent back these images:

Figure 4 — Julin Divider device.[10]

Figure 5 — Julin Divider device.[10]

Figure 6 — Julin Divider device is transported to the shot hole.[10]

Figure 7 — Julin Divider device is unloaded.[10]

Figure 8 — Julin Divider device is unloaded.[10]

Figure 9 — Julin Divider device before mounting on the shot rack.[10]

To the best of my knowledge, these are the only publicly available images of a US nuclear test device from the days of underground nuclear testing. There are several images of a reentry vehicle undergoing centrifuge testing in the Sandia underground nuclear testing photo collection on NARA, which I believe is the Bedrock Mast device (520 kt) that became the W87, but I lack firm evidence of this. Mast was a LANL test, but the secondary from the device was probably shared with the W88 and passed between the labs.

[2023-04-05: I somehow completely forgot that images of the W71 from the Cannikin test at Amchita exist, making this the second picture of a device from the underground testing era.]

From these images, we can determine that the Divider device is the W91, mounted in an SRAM-II/SRAM-T nose section. I say SRAM-II/SRAM-T, because I have not found any details on the difference between the two weapons, other than their warheads and roles. To the best of my knowledge, they are mostly identical except for the warheads.

To justify this statement, please look at this image of the SRAM-II (I have linked the image due to its uncertain copyright status). Notice that the warhead section is not conical and curves slightly towards the point, like the Divider device. It appears to be made of a grey/blue composite of some kind, with slight lines running along the axis of the weapon, like the Divider device. It also has a black tip, and a similar black ring can be seen on the Divider device where they lopped off the end.

Some of you may ask why the device is fitted inside the nose cone, and this is probably because the device is sensitive to changes in mass near the radiation case due to tamping. The W76 is an example of a weapon like this.[11, sec. 5–25]

These details, combined with the labs’ desire to create a W76 replacement at this time, strongly suggests that the Divider device was the W91.

After Divider

The planned follow-on to Divider was Icecap, to be fired in Spring 1993. The yield was planned to be in the 20 to 150 kt range.[12, p. 53] The test was to be a joint Atomic Weapons Establishment/Los Alamos test (AWE being the British nuclear weapons lab) examining low temperature performance of a weapon.[13]

What is interesting is that the diagnostics rack for the test is on site and can be seen in site tours.

Figure 10 — Icecap diagnostic rack.[14]

This rack has a warhead casing in it… a casing that looks like a W91 casing.

There is a better photo of this casing that looks identical to a W91, but the image is owned by CNET so I will only link it. I received some suggestions that they probably slapped any old casing in there for the tours, but I personally suspect that this is a casing identical to the real test that was used to check fit and alignment of the diagnostic rack.

Why the British were involved in a W91 test could be explained by British desires to also replace their W76 clone, Holbrook. While it is often claimed that Holbrook uses IHE, I personally suspect that it merely uses a safer explosive over PBX9501, probably EDC-37. The British use the same reentry vehicle as the US, so if the British could fit an IHE primary into the RV (IHE is generally lower in energy than conventional HEs), they would have.

Another explanation, which I find more likely, is that the British intended to replace their WE.177 gravity bombs with the W91. The Tactical Air-to-Surface Missile (TASM) program was cancelled in October 1993[15] and the WE.177A, planned to be retired in 2007, was retired in 1998. The TASM program was considering both the French ASMP missile, and SRAM.

The Future

It very hard to predict the future, but of any period of time since the end of the Cold War, the next few years are the most likely to see the US resume nuclear testing. I do not believe that the US would unilaterally resume testing, but given current international events, I would not be surprised to see Russia or China resume testing, and the US following suit.

Russia currently looks weak. Incredibly weak. Their abysmal conventional performance in Ukraine is beginning to lead people to question if Russia’s nuclear arsenal is in the same condition. I personally suspect not, as if there is only one place in the Russian military where the funds have not been completely stolen, it would be in Russia’s strategic missile forces.

But my personal view matters little. What actually matters is that people both inside and outside Russia believe that Russia’s nuclear arsenal works, and if people begin to doubt, Putin will need to prove otherwise. A nuclear test is a very convincing way to do so, and assuming minimal diagnostic requirements, could be done at relatively low cost. But the downside of such a barebones test is that they won’t be able to easily figure out what went wrong if the test produces unexpected results.

China may also return to nuclear testing. Over the last few years, they have increasingly demonstrated that they care little about what the international community thinks. They are also apparently expanding their arsenal, given the construction of hundreds of new missile silos.[16] They have also only conducted a relatively small number of tests compared to the other powers, so they may have gaps in their knowledge that they wish to fill. That said, I think it’s less likely than Russia — though Russia resuming testing may provide a convenient excuse for China to do so as well.

References

[1] ‘Sen. Mark O. Hatfield: Champion of Saner Nuclear Weapons Policies | Arms Control Association’. https://www.armscontrol.org/blog/2011-08-08/sen-mark-o-hatfield-champion-saner-nuclear-weapons-policies (accessed Oct. 29, 2022).

[2] Victor H Reis, ‘Post-Cold War U.S. Nuclear Strategy: A Search for Technical and Policy Common Ground’, National Academies Committee on International Security and Arms Control Public Symposium, Aug. 2004. Accessed: Oct. 29, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://sites.nationalacademies.org/cs/groups/pgasite/documents/webpage/pga_049760.pdf

[3] ‘30 years later, Hunters Trophy participants recall LLNL’s final underground nuclear test’, Sep. 19, 2022. https://www.llnl.gov/news/30-years-later-hunters-trophy-participants-recall-llnls-final-underground-nuclear-test (accessed Oct. 31, 2022).

[4] S S Hecker and J H Nuckolls, ‘Letter from Director Los Alamos to Secretary of Energy Hazel O’Leary’, May 1993. Accessed: Nov. 05, 2021. [Online]. Available: https://www.osti.gov/opennet/detail?osti-id=1042616

[5] ‘The US Nuclear Stockpile: Looking Ahead Drivers of, and Limits to, Change in a Test-Constrained Nuclear Stockpile’, Military Applications Group, Nuclear Weapons Stockpile Systems, Los Alamos National Laboratory, Mar. 1999. [Online]. Available: https://osf.io/ymjvu/

[6] Hochrein, G J and Muir, J F, ‘Heat Transfer and Boundary-Layer Transition Results for the Halberd FTU-1 Flight Test’, Sandia Labs., Albuquerque, N.Mex. (USA), SC-DR-70-578, Nov. 1970. Accessed: Jun. 28, 2021. [Online]. Available: https://www.osti.gov/opennet/detail?osti-id=16341079

[7] Chuck Hansen, Swords of Armageddon, vol. VII, 7 vols. 2007.

[8] D. Rondeau, ‘SRAM A alternate configuration study.’, Sandia National Labs., Albuquerque, NM.; Department of Energy, Washington, DC., DE92002214, 1991. Accessed: Oct. 30, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://ntrl.ntis.gov/NTRL/dashboard/searchResults/titleDetail/DE92002214.xhtml

[9] B. A. Steeves, ‘Last chance! Divider anniversary display in NSSB lobby ends Friday’, Los Alamos National Lab. (LANL), Los Alamos, NM (United States), LA-UR-22-30012, Sep. 2022. doi: 10.2172/1889959.

[10] Spivey, Whitney Jackson, McGuiness, Laura Lee, Steeves, Brye Ann, and Ziomek, Paul Roman, ‘30th Anniversary of Divider Display’, Los Alamos National Lab. (LANL), Los Alamos, NM (United States), LA-UR-22-29061, Aug. 2022.

[11] ‘Joint DoD/DoE Trident Mk4/Mk5 Reentry Body Alternate Warhead Phase 2 Feasibility Study Report’, Jan. 1994. [Online]. Available: https://osf.io/83sja

[12] ‘Nevada Test Site Guide’, National Nuclear Security Agency, DOE/NV-715 Rev 1, Mar. 2005. [Online]. Available: https://web.archive.org/web/20130224041627if_/http://www.nv.energy.gov/library/publications/historical/DOENV_715_Rev1.pdf

[13] ‘Icecap’, Nevada National Security Site (NNSS), North Las Vegas, NV (United States), NNSS-ICEC-U-0046-Rev01, May 2022. Accessed: Oct. 30, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.nnss.gov/docs/fact_sheets/NNSS-ICEC-U-0046-Rev01.pdf

[14] R. A. Meade, ‘LANL Photo Collage’, Los Alamos National Lab. (LANL), Los Alamos, NM (United States), LA-UR-18-29893, Oct. 2018. doi: 10.2172/1479881.

[15] ‘Missile system “no longer needed”: Christopher Bellamy looks at the reasons behind cancellation of the TASM project’, The Independent, Oct. 18, 1993. https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/politics/missile-system-no-longer-needed-christopher-bellamy-looks-at-the-reasons-behind-cancellation-of-the-tasm-project-1511708.html (accessed Oct. 30, 2022).

[16] B. Brimelow, ‘Why China changed its mind about nuclear weapons and is bulking up its arsenal at “accelerated” pace’, Business Insider. https://www.businessinsider.com/why-china-is-rapidly-expanding-its-nuclear-arsenal-2022-1 (accessed Nov. 01, 2022).