This blog begins with a fascination with the secret of the modern nuclear weapon.

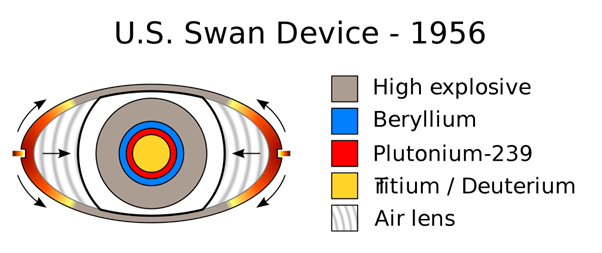

If you take a look at the work of the two greats of public nuclear weapons sleuthing; Chuck Hansen — the author of The Swords of Armageddon[1], and Carey Sublette — the author of the Nuclear Weapons Archive[2], you will find both argue that the secret of the modern, compact nuclear weapon is that of the two-point initiated air lens, also known publicly as the Swan device.

This device provides the spherical implosion shockwave needed to efficiently compress the nuclear weapon’s pit (generally made of either 239Pu or 235U, or a combination of both) to the necessary supercriticality so that a nuclear explosion can occur.

Credit: 0x24a537r9 – Licenced under CC Attribution-sharealike 3.0

The design itself is quite elegant; the detonation starts at each end of the weapon which causes a flyer plate made of some suitable metal to fly across the air gap as the explosive detonates from the ends towards the midpoint of the outer shell. With appropriate design of the device’s geometry, it’s possible to get all parts of the inwardly moving flyer plate to strike the surface of the high explosives around the pit at the same time, and the shock caused by the high-speed flyer plate striking the explosives the causes the explosives to detonate.

If you’re quite handy with the calculus, you can probably calculate the equation of the curve needed for a given explosive, slapper material and slapper thickness from the Gurney Equations yourself. Of course, actual practice is often different from the theoretical, but it’s likely a good starting point.

But this design has a number of issues.

The first is the string of safety issues with Swan. The best known of these relates to the W47 warhead that armed the Polaris A-1 and A-2 sea-launched ballistic missiles (SLBMs). At approximately 330kg in weight and with a yield of 600 kt in the Y1 version and 1200 kt in the Y2 version, the W47 was the first true lightweight thermonuclear weapon, and by 1966 — only six years after the weapon entered service — an estimated 75% of the W47s in service were believed to be duds. This was all because Lawrence Livermore National labs — the weapon’s designers — were forced to add a poorly tested mechanical safing device to the weapon’s primary shortly before the introduction into service because they could not design the weapon to be one-point safe due to the nuclear weapons test moratorium in place.[3, p. 412]

For those who are not familiar with nuclear weapons design, to be one-point safe is where a nuclear weapon won’t produce an appreciable nuclear yield (in the US context, “appreciable” being more than 4 lb of TNT equivalent) when detonated from a single point, such as what might occur in an accident. This is because while an almost spherical implosion is desirable to produce an efficient implosion assembled nuclear weapon, an uneven detonation can still compress the weapon pit to some level of supercriticality, which can produce small but not insignificant nuclear yields.[4]

So LLNL added a mechanical safing device, called Actuator, Nuclear Arming (ANA).[5, p. VI–65]

Mechanical safing was not a new concept; almost every implosion-type weapon produced between 1949 — starting with the Mark 4 bomb[6] — all the way up to 1957 with the introduction of the first sealed pit, one-point safe weapon — the W25 warhead for the AIR-2 Genie air-to-air rocket — used mechanical safing. Except, mechanical safing in this context was in-flight insertion, where the weapon pit was not placed into the implosion assembly until the weapons was to be used. With the Mark 4 bomb introduced in 1949, that meant a crew member had to physically load the pit into the weapon before use.[7]

Images of a British weapon of similar design to the Mark 4 undergoing manual insertion. Credit: UK MoD, with thanks to Casillic for uploading these.

Obviously, this was a less-than-ideal operation to perform on the ground, let alone in flight, so in 1952 the Mark 5 bomb was introduced which included a mechanical device that loaded the pit into the weapon at the push of a button, in flight.[8][7]

The automatic IFI device for the Mark 5. Credit: US DoD, with thanks to Casillic for uploading these.

In the W47 however, LLNL were very tightly constrained by size and weight requirements, so they went with a boron-alloy tape[3, p. 410] that was spooled inside the hollow weapon pit. At arming, a small electric motor would pull the wire out of the pit.[5] For those not aware, boron is a strong neutron poison i.e. it strongly absorbs neutrons while not contributing to a nuclear reaction. Boron is used in nuclear reactor control rods for this reason.

Unfortunately for LLNL, they did not foresee the tape (sometimes described as a wire) becoming brittle with age and shortly thereafter it was discovered that the wire would break during retraction, dudding a large fraction of the W47 stockpile. It’s hard to tell exactly when this problem was discovered, but the W47 Mod 1 warhead was design released in December of 1960, approximately eight months after the first EC (emergency capability) warhead was produced and six months after the first WR (war reserve i.e. production) warhead was produced. This was followed by a Mod 2 warhead in November 1962.[9] Either (or both) of these mods may be the result of trying to fix this issue.

But LLNL’s problem were not over, as during routine inspection in 1966 it was discovered that the weapon’s pits were corroding. It was eventually traced to the lubricant used on the mechanical safing wire, but at this point someone said enough and the W47 warheads that were not quickly retired received a completely new primary derived from the Polaris A-3 warhead, the W58.[10] This revised warhead was probably proof-tested at full yield in 1968 (either Crosstie Boxcar or Bowline Benham, both LLNL shots and both of the correct yield for a W47 test).

The Swan-type primary used in the W47 was reportedly codenamed Robin.[11] Other weapons using the Robin primary, such as the W45 warhead, shared this problem. In fact, of the weapons we know for certain that use Swan-type primaries, all suffered serious one point safety issues[4], and almost all of them were retired in the 1960s or early 1970s.

The second issue is an engineering problem: how do you support the central high explosives and pit in the weapon? This by-the-way is a very important question; the core parts of the device must not move or deform, and therefore must be well supported. This is no simple bit of engineering as you need to support it in a way that does not interfere with the flyer plate crucial to the device’s operation while being capable of surviving very high-G loadings.

Take for example the B61 bomb. This weapon is one of the most mass-produced nuclear weapons in the US arsenal, introduced in 1967 and as of 2021 they are gearing up to produce the Mod 12 version of the weapon. Four versions (the Mod 3, 4, 7 and 11) are in the current US active stockpile.

This weapon, just from parachute deployment, experiences 200 to 300 Gs[12], never mind the forces experienced by the B61 Mod 11 weapon which is a ground penetrating weapon. So, somehow you need to support the central portion of the device in a way that does not interfere with the flyer plate but also does not allow for any significant movement under incredible accelerations.

I won’t say it’s impossible, but I’ve not seen any reasonable explanations for how it could be achieved.

The third issue is one of performance: Swan-type devices are more voluminous than spherical systems, meaning a lower photon density inside the radiation case at the time of detonation. This only matters in thermonuclear weapons, where a higher radiation case volume and lower photon density means less energy transferred to the secondary stage and more energy wasted on the radiation case.

This issue isn’t as big as I initially assumed, as after conversing with Carey Sublette, he provided some numbers for a Swan-type IHE system. To initiate the IHE with a 3.5mm thick stainless-steel flyer, a velocity of 1560 m/s is required. His rough numbers produce an ovoid with an oblateness of 1.37 i.e. a device 1.37 times longer than it is wide. This is substantially less than the ~2 that early weapons like the W45 had.

I’m uncertain what performance increase an MPI system which would have an oblateness of 1, would see over a Swan-type system with an oblateness 1.37 in a thermonuclear weapon. It probably depends on the volume occupied by the secondary and interstage material, in the sense that it matters more with a very small secondary where internal volumes are small, and not very much with a very large secondary.

With the above in mind, I spent several years wondering what they were actually doing. One possibility that occurred to me was that they had simply dispensed with perfect implosion systems by doing away with explosive lenses. This may very well work as D-T boosting is the main fission driver in modern nuclear primaries, kicking in at a very small yield of 0.1 to 0.3 kt and providing most of the neutrons needed to fission the fuel and provide the remaining 5 to 10 kt of yield a modern thermonuclear primary produces.

The other thought I had was the use of mild detonating fuze (MDF). MDF is made by taking a metal tube such as made of aluminium, packing it with a high explosive such as PETN, and then drawing it through successive dies until the desired diameter is reached. Diameters under 2mm are possible and the drawing process creates a fuze with a very consistent detonation velocity. MDF is used in all sorts of things from spacecraft to ejections seats to conventional weapons, usually for transferring detonations from one location to another or for controlling timing in detonation chains.

When I suggested this to a researcher interested in British nuclear weapons history, their response was “oh, so you mean like Super Octopus?”. I had no idea what Super Octopus was, so I went looking.

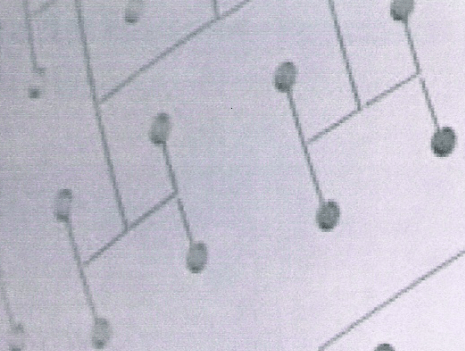

Brian Burnell’s site on nuclear weapons does an excellent job explaining the history of Super Octopus and its predecessor Octopus. Few technical details are included however, but the most significant is that Super Octopus is multi-point initiation (MPI) system, and a nice picture provided by the UK’s Atomic Weapons Establishment (AWE) hints at the idea.

Credit: Atomic Weapons Establishment.

From there it was possible for me to discover two things:

The first is that MPI systems are on the Australian Government’s sensitive export list. Items on that list are generally limited to items that threaten Australian interests, essentially things used to make nuclear, chemical or biological weapons, radar- and submarine-defeating technologies, parts useful for developing long-ranged missiles, guidance systems for missiles and equipment to make the aforementioned etc. The fact MPI is on the “special” list is of particular interest. A short search shows MPI technology is also on the controlled exports lists of many other nuclear and non-nuclear states as well.

The other thing I found was the report Shock Wave Generator for Iran’s Nuclear Weapons Program: More than a Feasibility Study from the Foundation for Defense of Democracies (FDD). The FDD styles themselves as a non-partisan thinktank on foreign policy and national security issues, but has been criticised as alarmist and warmongering. Regardless the organisation’s political views, the report itself explains quite clearly how an MPI system works and when combined with the AWE image, things start making a lot of sense.

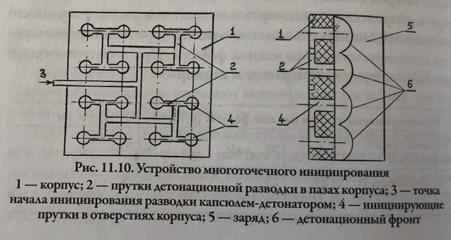

Probably the best explanation provided from the FDD report comes from a diagram published in the Russian explosives engineering journal Explosions: Physics, Engineering, Technology. The image is by Vyacheslav Danilenko, who is alleged to have provided technical assistance to Iran’s nuclear weapons program.

Credit: V V Danilenko in Explosions: Physics, Engineering, Technology (2010).

What is depicted here is called an H-tree. H-trees have an interesting property in that the distance from the centre of the tree (where the line marked 3 connects) to each end point (the holes marked 4) is the same for all end points. You can further add additional “H” branches to each end point, increasing the number of end points.

So, if you replace the lines on an H-tree with channels filled with high explosive, you can initiate the explosive at the centre-point of the tree, it will detonate along the paths, and then the detonation will reach each end point at the same time. If you examine the diagram, you can see the channels are grooves cut into the plate and that holes are drilled though it to transfer the detonation to the other side.

In effect, the diagram depicts what is called an explosive plane-wave generator.

Some of you may be looking at the diagram however and thinking that what is depicted is not a plane wave, but a bunch of spherically expanding waves. You are correct, but as the detonation wave travels away from the output face of the plane wave generator, the detonation wave quickly smooths out. Another researcher put together a model on the effect, based on the published work of several Russian researchers[13][14] and found that for a 300mm diameter primary, the detonation wave only needs to travel through a few tens of millimetres of explosives to smooth out using a modest <800 output MPI manifold, or a separation of about 20mm per output.

There are other questions about MPI systems that need to be addressed if they are used in modern weapons. The major one being how to make these systems suitable for use with insensitive high explosives (IHE). Conventional high explosives (CHEs) such as those based on PETN and HMX have very small minimum critical diameters, down to less than 0.5mm for PETN and approximately 1mm for HMX. Minimum critical diameter is important because it represents the minimum diameter your MPI channels can be before they no longer reliably propagate a detonation. For IHEs, the best critical diameters are as low as 6 mm unconfined, which limits the output density of your manifold.

I know of three possible solutions supported by the research directions we publicly know the US weapons labs have taken. These include conventional paste explosives pumped into the manifold as part of weapon arming, qualification of manifolds that contain conventional explosives as IHE through testing, and the development of CE manifolds that rely on explosive overdriving to initiate IHE. Paste explosives and qualifying CE MPI systems as IHE are supported by publicly available research going back to the early 1970s (which is about the same time as when IHE weapons were first developed), while overdriven systems are a novel development dating from the 2000s.

I’ll take a moment to explain overdriven systems because they are less intuitive (it is actually quite a fascinating topic). The system is based on having explosive outputs that individually are too small to initiate IHE and are instead clustered in two and threes, with each output in a cluster being fed from a separate MPI network. When all three networks are initiated with the correct timing, the detonation of each output cluster produces shockwave interference, which produces the pressures necessary to initiate the IHE. This allows for the use of a CHE MPI system, knowing that the initiation of a single pathway will not initiate the IHE.

A fourth possibility also exist: it may be possible to build manifolds using IHE. This is likely something that won’t be resolved by going through declassified information given how tightly the US government holds onto it. My plan is to eventually design and test it with computer modelling to see which solutions work and which do not.

But really, this blog isn’t about Super Octopus, it’s about all the other things I’ve found during my research looking for evidence of Super Octopus. I intend to publish my research into US use of Super Octopus more formally, when I actually have sufficient evidence to prove it.

References

[1] Chuck Hansen, Swords of Armageddon. 2007.

[2] Carey Sublette, ‘The Nuclear Weapon Archive – A Guide to Nuclear Weapons’. http://nuclearweaponarchive.org/ (accessed Aug. 18, 2021).

[3] Chuck Hansen, ‘W47 Polaris’, in Swords of Armageddon, vol. VI, 2007.

[4] G. H. Miller, P. S. Brown, and C. T. Alonso, ‘Report to Congress on stockpile reliability, weapon remanufacture, and the role of nuclear testing’, Lawrence Livermore National Lab., CA (USA), UCRL-53822, Oct. 1987. doi: 10.2172/6032983.

[5] Betty L Perkins, Tracing the Origins of the W76: 1966-Spring 1973. Los Alamos National Labs, 2003. Accessed: Jul. 23, 2021. [Online]. Available: http://archive.org/details/DeclassifiedNuclearWeaponDevelopmentHistoryReports

[6] ‘History of the Mark 4 Bomb’, Sandia National Labs., Albuquerque, NM (USA), SC-M-67-544, Feb. 1967. [Online]. Available: https://osf.io/46sfd/

[7] R N Brodie, ‘A Review of the US Nuclear Weapon Safety Program – 1945 to 1986’, Sandia National Labs., Albuquerque, NM (USA), SAND86-2955, Feb. 1987.

[8] ‘History of the Mark 5 bomb’, Sandia National Labs., Albuquerque, NM (USA), SC-M-67-545, Mar. 1967. [Online]. Available: https://osf.io/84trf/

[9] ‘History of the Mark 47 Warhead’, Sandia National Labs., Albuquerque, NM (USA), SC-M-67-679, Feb. 1968. [Online]. Available: https://osf.io/fytcp/

[10] S. Francis, ‘Warhead politics : Livermore and the competitive system of nuclear weapons design’, Thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 1995. Accessed: Aug. 10, 2021. [Online]. Available: https://dspace.mit.edu/handle/1721.1/10589

[11] C. Hansen, ‘Beware the Old Story’, Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, vol. 57, no. 2, pp. 52–55, Mar. 2001, doi: 10.2968/057002015.

[12] ‘History of the TX-61 Bomb’, Sandia National Labs., Albuquerque, NM (USA), SC-M-71-0339, Aug. 1971. [Online]. Available: https://osf.io/bfjrc/

[13] V. A. Sosikov, S. I. Torunov, and S. V. Dudin, ‘Smoothing the front of the detonation wave in experiments with multipoint initiation’, J. Phys.: Conf. Ser., vol. 1147, p. 012027, Jan. 2019, doi: 10.1088/1742-6596/1147/1/012027.

[14] A. V. Shutov, V. G. Sultanov, and S. V. Dudin, ‘Mathematical modeling of converging detonation waves at multipoint initiation’, J. Phys.: Conf. Ser., vol. 774, p. 012075, Nov. 2016, doi: 10.1088/1742-6596/774/1/012075.